Huston, Things Are Heating Up: A Call for Capturing CO2

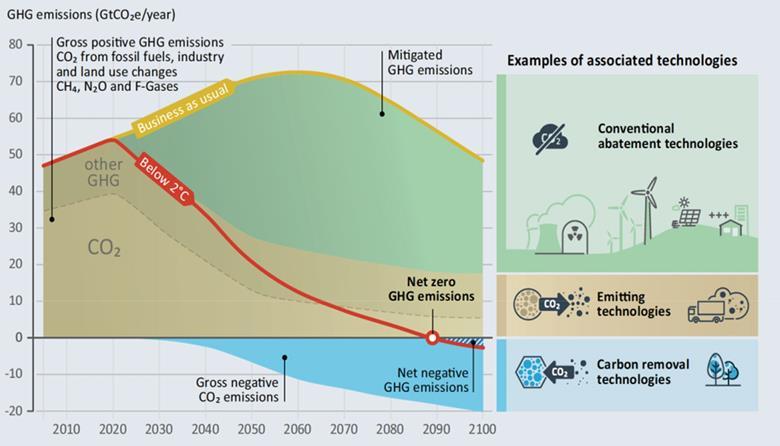

Limiting warming to no more than two degrees has become the de facto target for global climate policy. To actually achieve this, we will need to dramatically reduce our current emissions and simultaneously be able to remove about 10 to 15 gigatons of CO2 every year by the year 2050.

Before we really go into the matter of this article, I quickly would like to lay out my intentions. The reason for writing this piece and making it publicly available is that I want to share my personal learning of the last months and hopefully thereby providing you help in one way or the other and foster a reasonable understanding of the very basics of carbon removal.

At the end of this article, you can find a couple of primary sources and places you might wanna follow up with after the read.

On an important note: The used and linked resources are by no means exhaustive. Additionally, the things written in this article may very well contain errors and misleading information alongside typos. So, if you find important factual errors, feel free to reach out so that I can correct and provide valid and meaningful information to people who would like to properly educate themselves on the topic. At this point, thank you in advance.

The essence

Ever since the industrial revolution, people have been burning an incredible amount of stuff. More and more every year. The things we burn range from nice little campfires to big fires in power plants. In all these cases we’re emitting greenhouse gases. And we do this at a scale which is enough to cause change in the thermal properties of the atmosphere, resulting in higher heat. In short: This is the greenhouse effect, which is the major contributor to climate change.

Let’s get back to the origins of carbon emissions. Besides power and transportation, there are various, for many people probably less obvious emissions sources too. Some of these include the production of heavy metals, cement, but also agriculture (soil nitrous oxide and animal methane), industrial and permafrost methane leaks as well as others.

Some of these sectors have more or less clear paths to reduce emissions (electric vehicles, solar/wind/nuclear) and some will be slower or more complex to decarbonize (air travel, industrial emissions, some agricultural emissions and methane).

Climate models try to describe how much warming we can expect in different emissions reductions scenarios. When talking about these scenarios, a temperature increase of only 1.5 degrees C is now considered a truly optimistic target that would require unprecedented carbon emission reduction. 2 degrees seems to be difficult but in reach and 3+ degrees would be a worst-case scenario. These different scenarios are described by “Representative Concentration Pathways”. The scenario of a temperature increase of 2 degrees is internationally agreed upon as a maximum acceptable risk.

So, what can we do about it? There are basically two obvious approaches to keep warming below certain levels: Either we reduce emissions, or we figure out ways, how to remove previous emissions from the sky.

If there’s one thing from this article to truly remember, it should be that we really need to do both. Because the days where optimistic emissions reductions kept us below a 2 degree global warming target are definitely gone.

Figure S.1 from Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration (2019)

So, as mentioned already, in order to keep below 2 degrees, we will need to substantially reduce our current emissions and at the same time, remove round about 10 to 15 gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere every year by 2050. But this is not it yet. We also need to be able to scale our removal efforts over the years so that in the year 2100, we can remove +20 gigatons annually. The quantity we need to remove year by year afterwards is highly dependent on our ability to reduce our emissions quickly.

A better feeling of the scale

Here’s where we ae at in terms of global temperatures:

Now that you have a greater sense for the change of average global temperatures, let’s try to also make more sense out of the root cause. Greenhouse gas emissions are described in units of tons. It’s hard to think about how much a ton of gas really is. At least it was for me. The following picture shows how “big” this is at surface temperature and pressure:

Another good illustration is the this animated video which visualizes New York City’s emissions per hour, day and year with these one-ton ball representations.

To put things in perspective in your country, see the following map with emissions per capita:

If you’re interested in getting an idea about your approximate carbon footprint, you can have a look at Wren’s calculator that asks you about your commuting habits, flights and diet to infer a ballpark number. In this context, you also might want to dig into Erika Reinhardt’s detailed guide on how you can reduce your emissions.

Another way people are talking about CO2 is, for example, “300 parts per million CO2”. People thereby reference to the concentrations of the emitted gas as a portion of the atmosphere. This is important to know as climate modeling is based on these concentrations.

To put the numbers above in perspective (credits to Klaus Lackner for the distillation), 1 ppm equals about 7.5 gigatons of carbon dioxide. However, roughly half of the CO2 intermingles into the surface ocean and some goes into the biosphere. So, in our example, the net result is that it takes about 15 gigatons of CO2 to raise the atmospheric concentration by 1 ppm. And we currently raise it by around 2.5 ppm per year.

Introduction to units and measurements

How to measure greenhouse gases

As touched upon already, greenhouse gases are released by burning stuff as well as the product of other chemical reactions in the industry sector. In this context, we are mainly talking about carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). CH4 and N2O are more potent greenhouse gases which occur in an order of magnitude less quantity than CO2. That’s why removing these two compounds is much more difficult. Additionally, CH4 also has a much shorter half-life in the atmosphere than CO2 does.

The units you will normally encounter

Tons of CO2

This is the most common unit and simply stands for a ton of CO2 by mass. That’s it. It’s often unclear though whether someone means metric or imperial tons. However, as the difference is only 2%, in most cases, the ambiguity is not a problem.

Tons of CO2E

CO2E is something you often see when reading about offsets or macro-scale emissions comparisons. “Equivalent” means another greenhouse gas, normalized to the warming potential of CO2. For example, methane gas is about 28-36x equivalent (GWP 100). In order words, 1 ton of methane would count as 28-36 tons CO2E.

Tons of C

This measurement is mostly used when talking about sinking carbon in plants and soils and simply means we only measure the C in the CO2, mapping 3:11 by molar mass. This as the atomic weight of carbos is 12 atomic mass units, while the weight of carbon dioxide is 44, because it includes two oxygen atoms that each weigh 16. In short: one ton of carbon equals 44/12 or 11/3 tons of carbon dioxide.

Talking about megatons and gigatons

To keep things short: megaton = one million tons and one gigaton = one billion tons.

Greenhouse gases when mixed with the sky

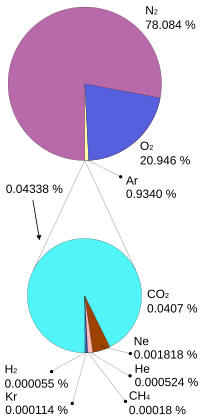

The atmosphere is made of a mixture of gases:

Source: Wikipedia Atmosphere of Earth

As you can see, greenhouse gases are a super small part of it. That’s why instead of describing tiny absolute percentages, we use these units to describe how much:

Parts per million (ppm)

Used in the context of CO2.

Parts per billion (ppb)

Used in the context of CH4, CFCs and other trace gases. This should clearly showcase the magnitude by which methane is more dilute than CO2.

This measurement should also illustrate why removing CO2 is an expensive proposition. Thermodynamically and thus monetarily. It’s a phenomenally dilute gas which means we have to separate a tiny fraction of the air from the rest of the air.

After this quick introduction into units and measurements, it’s time to take a step back. Cause the sensitivity of this system is really staggering. Already less than a basis point (one basis point = 1%) more absolute concentration of a trace gas in our atmosphere comes with ramifications that change the lives of people around the world.

Do we truly need to remove CO2?

Before the new century, negative emissions were not mainstream apart from some early research by David Keith, Klaus Lackner, among other. There was yet some combination of optimism that the problem wasn’t actually so bad, that the world would basically decarbonize at a sufficient rate that negative emissions wouldn’t be necessary and that an appropriate policy framework would force action. Action in the form of, for example, large scale carbon price or cap and trade, which today, still doesn’t exist worldwide. On top of that, there was fear that negative emissions present a moral hazard by giving ourselves “a way out” or workaround for crucial emissions reduction efforts. Click here for a good summary of the history.

In order to hit the 2 degree global warming target, the Paris Agreement calls on countries to set “Nationally Determined Contributions” or in short NDCs. These are commitments to a specific amount of CO2 emissions reduction over the coming decades. However, these commitments are actually not even close to enough as you can see below:

Source: CarbonBrief

Some scary stuff about this chart

- All the existing NDCs included in the chart don’t get us even close to the 2 degree trajectory

- Almost any country is even close to on being on track to comply with these commitments. To make things worse: each of the countries faces minimal to zero official consequences for failing to do so.

If we would want to limit warming to 1.5 degrees

Source: CarbonBrief

Source: CarbonBrief

Resulting in the following

Figure S.1 from Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration (2019)

Another aspect that is rather concerning is that research efforts into negative emissions technologies (NETs) have been significantly underfunded relative to their importance given the data we have. Also see this statement by the National Academies:

“…the federal government spent more than $22 billion on renewable energy research and development from 1978 to 2013. NETs have not received comparable public investment despite expectations that they might provide ~30 percent of the net emissions reductions required this century (i.e., maxima of 20 Gt/y CO2 of negative emissions and 50 Gt/y CO2 of mitigation in Figure S.1). NETs are essential to offset greenhouse gas emissions that cannot be eliminated, such as a large fraction of agricultural nitrous oxide and methane emissions.”

Taking CO2 out of the sky

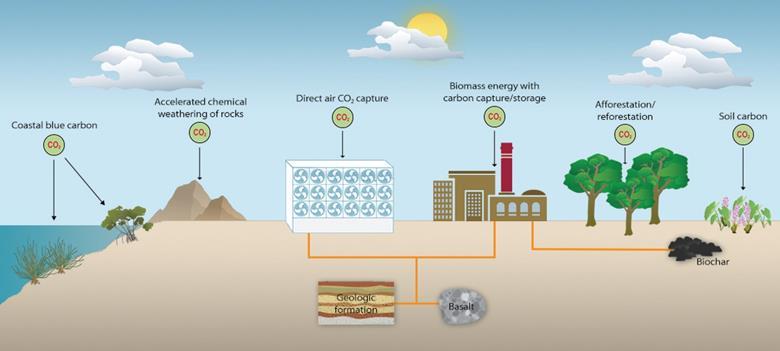

In short: there are plant-based, mineral-based and chemical options to remove CO2 from the sky.

Plant-based solutions leverage a plant’s capacity to capture carbon via photosynthesis and the energy of the sun. Solutions in this space include forestation and reforestation, soil carbon sequestration, algae or kelp farming and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, often referred to as BECCS. The latter is basically a biomass power plant that burns wood and then is fitted with a carbon capture device to handle the smoke or “flue gas”).

Mineral-based solutions are looking at speeding the weathering of naturally occurring rocks, e.g. Olivine.

Chemical solutions focus on Direct Air Capture also DAC (usually linked with geologic storage), where a rather big machinery sucks CO2 out of the air, providing gaseous concentrated CO2 that can then be injected underground for storage.

For a more comprehensive but still accessible overview, I can recommend Adam Marblestone’s Climate Technology Primer and primary sources at the bottom reference list, especially the summary section of the National Academies Report.

Figure S.1 from Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration (2019)

As you most likely can imagine, these solutions all have certain trade-offs, various potential for scaling, different cost implications and so on. To give you a little bit of an idea, here’s a graphic showcasing the cost to potential relation of the different solution approaches. Note: The figure references a 1.5-degree target and is merely a relatively simple way to give more context.

Source: InsideClimate News

A little overview on these solution approaches

Trees and forests

Photo by Dave Hoefler

Both trees and plants are incredible at carbon capturing. And they are doing so for “free” via the energy of the sun. It doesn’t matter how dilute CO2 is in the earth’s atmosphere. However, of course the CO2 that trees and plants absorb doesn’t just magically go away. What happens instead is that the C becomes part of the biomass of the tree or plant. That’s why whenever a tree or plant burns down, the carbon it captured is released into the air again. For permanent sequestration, we have to do something with the biomass of the forest. We could for example transform it into wooden building materials, biochar fertilizer or just drop it in the ocean. Another possibility would of course be to just let it grow for centuries. This, however, requires a well-managed cultivation of the forest. If we are able to do so, we can consider the sequestration enduring as long as that kind of management persists and is monitored.

But how are we actually able to measure how much carbon is captured this way? To understand this, scientists build models that relate easy-to-measure physical properties like diameter and height to the actual above-ground dry weight of a tree. We estimate that about 50% of this is carbon. These are generally known as the allometric equations. But there are also relatively modern techniques leveraging remote sensing and LIDAR which are being analyzed to do the same thing but in a more efficient way. There are various papers you can dig into if you’re interested to learn more.

An important fact about forests is that they do have a great impact on albedo, which is the ability to reflect solar radiation back to space. The darker a forest, the more it may actually decrease its albedo, “decreasing the forest’s utility” and causing warming (to read more, here’s a good paper). Additionally, when cultivating much bigger areas of forest, there may also be impacts on the biodiversity of the ecosystem the land would otherwise be used for.

Direct air capture (DAC) + sequestration

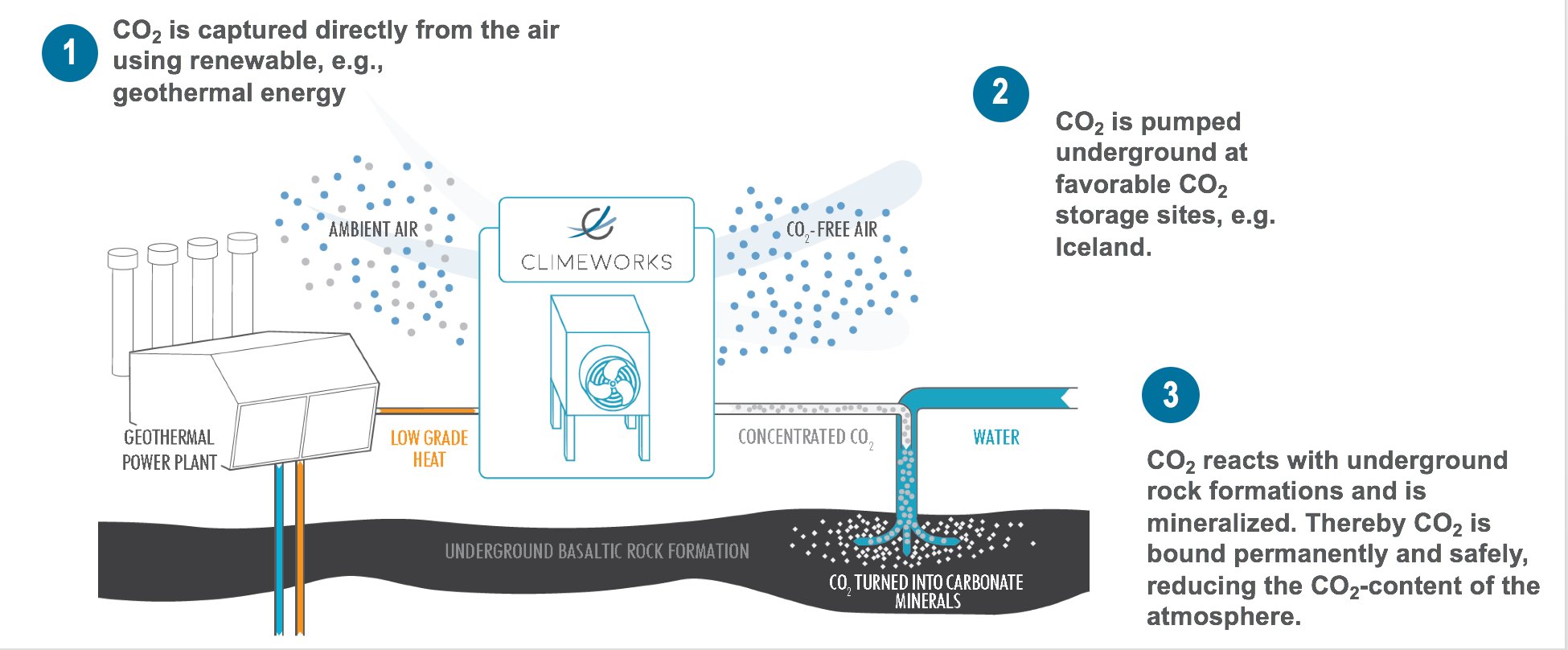

DAC from Climeworks

Traditional DAC facilities pass atmospheric air through a sorbent that absorbs, concentrates and then controls release of carbon dioxide. For a pretty detailed and still accessible overview of this kind of approach, read the article “The Role of Direct Air Capture in Mitigation of Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Emissions”.

One of the companies who are working on this is the Swiss-based startup Climeworks. Another one is, for example, Carbon Engineering. As promising as these efforts are, we have to mention that because carbon dioxide is so dilute (round about 0.04% in atmospheric air), these endeavors are rather energy intensive (22kJ/mol). Therefore, lifecycle analysis is important. One methodology can be seen in Keith et al. 2018. A paper which describes Carbon Engineering’s technical approach.

Additionally, there are some new DAC approaches, which are currently in the research phase. One of them being electro-swing adsorption (click here for the paper).

Independent of methodology, the result of DAC is pure gaseous carbon dioxide, which can be utilized or sequestered.

Sequestration

Sequestering CO2 means basically permanently removing the it from the carbon cycle and thereby reducing the concentration of CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere. This can be done by injecting the CO2 injected underground into an oil well, salt dome or a saline aquifer.

Source: The Role of Direct Air Capture in Mitigation of Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Emissions

One of the well-known initiatives in this context is called Carbfix. Carbfix started out as a project back in 2006 and was formalized by four founding partners in 2007, Reykjavík Energy, the University of Iceland, CNRS in Toulouse and the Earth Institute at Columbia University. Since then, several universities and research institutes have participated in the project under the scope of EU funded sub-projects, including Amphos 21, Climeworks and the University of Copenhagen.

The image below shows one of these sites where the transformation is carried out.

Source: The Role of Direct Air Capture in Mitigation of Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The whole process of capturing CO2 and pumping it into geologic storages is fairly simple to measure. Other than that, there are generally accepted practices in the oil industry to demonstrate secure storage.

Utilization

As mentioned before, the other thing we can do with captured CO2 is basically use it. Some of the purposes we can use it for can be considered negative emissions/long-term sequestration. To give you some examples, the hardening of cement could be one of these or making fuel and other chemicals. Some of these cases are of course much more interesting than others. Fuel probably being one of the most interesting ones given that it wouldn’t lead to an absolute increase in CO2 in the air compared to fuel pumped from the ground.

Whatever the use cases are, the upstream production or procedure costs matter. That’s also why, at least at this point, none of the mentioned usage purposes included DAC captured CO2. It simply makes no economic sense.

Soils

Photo by Paul Mocan

Soil carbon sequestration methods, on the other hand, want to encourage modified agricultural techniques that can increase the carbon sequestered in soil without affecting yield. A good starting point to dig deeper into the matter, you can read this article here.

Such mechanisms include no-till farming, which is having an impact on the usage of nitrogen fertilizers. This in turn can enable storage in soil of some of the plant’s carbon volume.

Measuring soil carbon tends to be quite complex and to mention that as well, has high variance. Cause there’s carbon that is in the biomass of plant roots, but there’s also carbon excreted by them and that at some point becomes stable in the soil. The latter is called soil organic carbon. Such measurements tend to be really expensive. And other technologies that address this are yet very young and at an early stage in their development. Carbon remote sensing being one of them.

Remote sensing is hard in this context as you don’t just care about the carbon content of the topsoil, but you also do care about the distribution of carbon vertically down the soil column for a couple feet. This because usually, the deeper the carbon is, the more enduring it is stored.

Another common method inverse modeling. With this approach you try make an extrapolation of the soil organic carbon based on the plant growth. More plant growth usually translates into more soil organic carbon. But there’s by no means a perfect correlation that would make this a more rigorous method.

Should you be generally interested in learning more about this particular topic, I highly encourage you to have a look at the work and programs by the Colorado State University.

Bio energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and biochar

BECCS

Photo by Andrei Merkulov

The whole idea behind biomass power is to burn biomass that previously has been part of the CO2 in the atmosphere instead of using coal or natural gas. In some sense, BECCS combines the “for free” capturing of plant-based mechanisms and the sequester idea often applied to CO2 resulting from DAC.

As a consequence, BECCS strengths and weaknesses are more or less similar to the ones of forests. The land required for such plants is rather large. Other than that, BECCS requires a high volume of biomass. This is therefore a great opportunity for sequestration. However, such plants are currently mostly deployed at smaller scale.

The product of the process depends on how the plant combusts or pyrolyzes biomass. Specifically, you either end up with a stream of flue gas from which you can concentrate the carbon and do geologic storage, utilization or anything else you can do with flue gas. Some companies like Charm, for example, are able to keep C in the biomass by applying pyrolysis and thereby output biochar.

Biochar

Photo: Art Donnelly / seachar.org

As just touched upon, another option is simply taking biomass and making biochar out of it, usually by doing pyrolysis.

So, what you do is you heat the biomass to within a low-oxygen environment. Thereby, you transform the biomass into a chalky black material that almost pure carbon.

This product can then be used as fertilizer respectively soil additive, improving fertility, increase SOC and reduce soil heavy metal concentrations. For those of you who are interested to learn more about the details here, can do so by starting here in the section “Biochar Additions”.

So again, high quality biochar usually has the potential to remain enduring for quite a long time period as it should keep the C sequestered. It’s important to mention though that its stability is influenced by similar environmental conditions and effects as SOC. Especially by precipitation and soil water content because of the related microbial decay.

In addition its capability to sequestrate C, biochar seems to also have a positive effect on the greenhouse gas effect by reducing soil N20 emissions.

Enhanced weathering and carbon mineralization

People who are into technical aspects should have a read on “An Overview of the Status and Challenges of CO2 Storage in Minerals and Geological Formations”.

Enhanced weathering - Ex-situ mineral carbonation

Enhanced weathering is all about geoengineering approaches using dissolution of natural or artificially created minerals for the removal carbon dioxide.

This works as common rocks form carbonate minerals when exposed to CO2. Even at atmospheric concentrations. In the process, they permanently bind the C as a mineral - CaCO3 calcium carbonate.

Theoretically, this phenomenon could restore earth to pre-industrial CO2 levels. That’s why enhanced weathering basically tries to radically accelerate this natural phenomenon. People regularly call this process ex situ mineralization as you are mining rocks and putting them through a sped-up carbon mineralization process aboveground.

Source: Project Vesta

As you might know, some rocks’ capabilities for binding carbon dioxide are more effective than others. Olivine and serpentinite, for example, are rocks that are much more promising. In general, the amount of carbon they capture is proportional to the amount of surface area exposed to air. Hence, what we want is a low-energy way to grind them to a particle size, optimized to bind carbon. As interesting and promising this methodology might be, much more research is needed to explore the exact kinetics of the process and its risks.

Geologic sequestration - In-situ mineral carbonation

Source: GRT Group

In contrast to the enhanced weathering, in-situ mineralization can be understood as the geologic sequestration process that’s crucial to DAC systems.

The way this works is by injecting a stream of carbon dioxide into certain sots of geologic formations, thereby permanently storing the CO2 in a mineral. So, what you do is you’re injecting CO2 to where the rock already is. Hence, in-situ rather than ex-situ, which is bringing the rock above ground and exposing it to atmospheric air.

Lifecycle analysis and trade-offs related to carbon removal strategies

As briefly mentioned before already, it’s important to always look at carbon removal solutions with a full lifecycle analysis in mind. Meaning, you should assess if the solution really a net-negative solution.

To make an example, when assessing BECCS as a solution, such an in-depth analysis would include the greenhouse gas emissions to grow the required biomass, the emissions of building the BEECS infrastructure, the emissions for biomass transportation, CO2 losses due to inefficiencies in carbon capture systems as well as the emissions emanating from the operations, e.g. the energy required for running the CO2 pumping machine, etc. If these emission sources all added up represent a smaller amount of CO2 than the volume a BECCS plant sequestered, you have a net-negative solution. Ideally, such emissions represent a very small fraction compared to the sequestration amount.

The lifecycle analysis is not the only assessment dimension though. There are a number of other dimensions. However, many of them are rather simplistic ways of evaluating procedures. Nevertheless, they can be beneficial and helpful for thinking about this quite complex problem space.

Some of the critical dimensions to evaluate and related questions are (by no means exhaustive):

Efficiency of capture systems

-

Does the way we capture carbon truly have a carbon negative lifecycle?

-

What are the projected trends over time and what are the implications on our cost basis?

Stability of storage

-

Once captured, how stabile is our storage methodology and what do we need to do to keep the carbon from re-entering the atmosphere?

-

What are the costs of the efforts required to store it permanently?

Measurability

-

What’s our confidence with respect to of how sure we are about the amount we are sequestering?

-

How reliable are our methods to measure potential leaks?

Opportunity costs

- What are the opportunity costs for the resources required for our endeavors?

Scaling

-

What are anticipated scaling possibilities and effects?

-

How much cost grind down is feasible and how quickly can we move on the learning curve?

-

What might be inflections of innovation and adoption over time?

Constraints and tail risks

-

What are potential risks related to the geology of the ground where we inject CO2?

-

How can political and policy changes affect existing programs?

-

In what way might unexpected scenarios affect a society’s confiscation of land?

-

How can climate change and its ramifications affect our solution approach’s effectiveness?

-

What if assumptions turn out to be wrong?

Let’s come to an end

This a very brief introduction into the topic of CO2 and the ways to go about solving the related problem of greenhouse gas effect. As a consequence, there are many interesting and important aspect that we haven’t yet covered in full detail or even at all. Some of these include solar radiation management, ocean fertilization and limiting, direct ocean carbon capture, unit economics of carbon removal solutions, policies, solution financing, bioengineering and more.

What you should take with you from all the things we did cover, is the following:

-

If we are really serious about keeping the 2-degree limit or at least close to it, 10-gigaton-scale negative emissions are a must in essentially every emissions reduction scenario. At this point in time, we are not even close to being on track for such.

-

For various reasons, negative emission solutions have been dramatically underfunded given their importance. Fixing this asap is of greatest importance if we want to have a shot at realizing cost reductions that are required for enabling us to successfully deploy solutions for our 10-gigaton-scale quickly enough.

-

Our solution approach should most likely include a solution portfolio. Cause no one category of technology or natural process will scale well enough to be sufficient.

-

We are slowly waking up to one of the most defining problems of our generations. And it’s a serious threat for the entire human species. What I find very interesting is that the problem context - climate - encompasses physics, chemistry, ecology, geology, policy, technology, human rights and other dimensions. Devoting ourselves fully to understanding the different parts and their interplay is therefore not only a must in order to solve the problem, but it’s also a tremendous opportunity for human progress. In that sense, let’s solve this together!

Resources

Overview reports:

- National Academies of Sciences:

- Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda (2019)

- IOP Environmental Research Letters:

- Negative emissions—Part 1: Research landscape and synthesis

- Negative emissions—Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects

- Negative emissions—Part 3: Innovation and upscaling

- European Academies Science Advisory Council:

- Negative emission technologies: What role in meeting Paris Agreement targets? (2018)

- IPCC:

- AR5 Synthesis Report - Climate Change 2014

- Visual feature: The Emissions Gap Report 2019

- Carbon180’s New Carbon Economy Report

- Editorial: The Role of Negative Emission Technologies in Addressing Our Climate Goals

- Engineered CO2 Removal, Climate Restoration, and Humility

- Getting To Neutral: Options for Negative - Carbon Emissions in California

- CarbonShot: Creating Options for Carbon Removal at Scale in the United States

- When are negative emissions negative emissions?

Blog posts:

Statistical overview

Journal: